Research News

Scientists obtain comprehensive view of agricultural ecosystems

June 20, 2017

Find related stories on NSF’s Critical Zone Observatories at this link.

Corn is grown not only for food; it is also used as an important renewable energy source. But renewable biofuels can come with hidden economic and environmental issues.

The question of whether corn is better used as food or as biofuel has persisted since ethanol came into use. Now, for the first time, researchers have quantified and compared these issues in terms of the economics of the entire production system to determine if the benefits of biofuel corn outweigh the costs.

Scientists Praveen Kumar and Meredith Richardson of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign published their findings this week in the American Geophysical Union journal Earth’s Future.

The results show that using biofuel corn doesn’t completely offset the environmental effects of producing that corn.

As part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) project to study the environmental effects of agriculture in the U.S., the Illinois researchers obtained a comprehensive view of agricultural ecosystems to analyze crops’ effects on the environment in monetary terms.

The research was conducted as part of NSF’s Intensively Managed Landscapes Critical Zone Observatory (CZO), one of a network of nine NSF CZOs across the country.

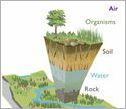

“The critical zone, where we focused our work, is the permeable layer of the landscape near the surface that stretches from the top of the tree canopy down to groundwater,” Kumar said. “The human energy and resource input involved in agriculture production alters the composition of this critical zone, which we were able to convert into a social cost.”

Added Richard Yuretich, NSF CZO program director, “using corn as a fuel source seems to be an easy path to renewable energy. However, this research shows that the environmental costs are much greater, and the benefits fewer, than using corn for food.”

The researchers took several steps to compare the energy efficiency and environmental effects of corn production and processing for food and for biofuel. They inventoried the required resources, then determined the economic and environmental effects of using those resources — defined in terms of energy available and expended, and normalized to cost in U.S. dollars.

“There are a lot of abstract concepts to contend with when discussing human-induced effects in the critical zone in agricultural areas,” Richardson said. “We want to present them in a way that shows the equivalent dollar value of the human energy used in agricultural production, and how much we gain when corn is used as food versus biofuel.”

Kumar and Richardson accounted for numerous factors in their analysis, including the energy required to prepare and maintain the landscape for agricultural production for corn and its conversion to biofuel.

The scientists quantified the environmental effects in terms of critical zone services, including impacts on the atmosphere and on water quality, and looked at corn’s societal value both as food and fuel.

“One of the key factors lies in the soil,” Richardson said. The assessment considered both short-term and long-term soil effects, such as on nutrients and carbon storage.

“We found that most of the environmental effects came from soil nutrients,” said Richardson. “Soil’s role is often overlooked in this type of assessment, and viewing the landscape as a critical zone forces us to include that.”

—

Cheryl Dybas,

NSF

(703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov

—

Lois Yoksoulian,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

(217) 244-2788 leyok@illinois.edu

-

NSF maintains a network of nine Critical Zone Observatories (CZOs) across the country.

Credit and Larger Version -

Where rock meets life: Researchers at NSF’s Critical Zone Observatories study Earth’s surface.

Credit and Larger Version -

Scientists affiliated with NSF’s Intensively Managed Landscapes CZO track land-use changes.

Credit and Larger Version -

Planter used for agriculture in an intensively managed landscape.

Credit and Larger Version -

Farm fields in the Midwest often have tile drains under them; the drains are nutrient conduits.

Credit and Larger Version

Investigators

Alison Anders

Praveen Kumar

Timothy Filley

Elmer Bettis III

Thanos Papanicolaou

Related Institutions/Organizations

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Related Awards

#1331906 Critical Zone Observatory for Intensively Managed Landscapes (IML-CZO)

Total Grants

$3,926,364