Research News

Sustainable Deltas Project researchers focus on importance of deltas across globe

June 7, 2016

Delta: A place where sediment carried downstream by a river enters the sea, forming a fan of sand or mud.

Although deltas make up just 1 percent of the world’s land, they’re home to more than half a billion people — and to fertile ecosystems such as mangroves and marshes.

Deltas also serve as economic hotspots, says hydrologist Efi Foufoula-Georgiou of the University of Minnesota. They support much of the world’s fisheries, forest products and agriculture, and are food baskets for many nations.

“They’re also ports of entry fostering growing cities and harbors,” Foufoula-Georgiou says.

Scientists have found that deltas are disappearing at an alarming rate, however, affecting humans and many other species.

“Deltas around the world play a significant role in providing local, regional and global human communities with agricultural and fisheries resources,” says Maria Uhle, program director for international activities in the National Science Foundation (NSF) Directorate for Geosciences, which funds Foufoula-Georgiou’s research. “The delta regions of Asia, for example, supply rice to a large percentage of the people who rely on it as a food staple.”

Water and sediment: Lifeblood of a delta

Human actions rob deltas of their lifeblood: water and sediment. On a global scale, people have diverted more than 40 percent of river discharges and 26 percent of river sediments into large reservoirs.

“Deltas are sensitive indicators of changing conditions,” says Tom Torgersen, program director in NSF’s Division of Earth Sciences, which also funds Foufoula-Georgiou’s research. “They respond to the effects of humans on the environment, including changes in river flows and sea levels.”

Losses of wetlands to development, and the erosion that follows, further deplete deltas of sediment. “Sea level rise accelerates the losses,” says Foufoula-Georgiou. “Hurricanes are often the death knell, cutting new channels and washing away huge amounts of mud and sand.”

To find out how deltas around the world are faring, Foufoula-Georgiou and her colleagues are studying the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) Delta, a vast fan that stretches across Bangladesh into West Bengal, India. Their work is part of the NSF-supported Sustainable Deltas Project.

Despite its size, the GBM Delta is foundering. The delta is sinking, with water covering its land surfaces four times faster than sea level is rising.

“Sediment would normally help build up the delta,” Foufoula-Georgiou says. But human land use upriver reduces the amount of sediment carried downstream. A further insult comes from shrimp farming, which modifies delta channels and results in yet more loss of land.

Almost 150 million people live in the GBM region. “Most of them rely on the delta’s natural resources,” Foufoula-Georgiou says, “so they, as well as the wildlife that depends on the delta’s rich sediment, are literally losing ground.”

The scene is far from unusual. Much of the sediment has been cut off from deltas across Asia. India has seen a 50 percent reduction for the Brahmani Delta, a 74 percent reduction for the Mahanadi, and a 94 percent reduction for the Krishna.

Nursery grounds for fish, bulwarks against storms

Deltas provide important nursery grounds for many fish species, and support both subsistence and commercial fisheries. They’re also prime places for people to settle. Popularity isn’t always a good thing, however.

“The catastrophic effects of floods in deltas were clearly demonstrated by Hurricane Katrina in the U.S.,” says Foufoula-Georgiou. Katrina resulted in costs estimated at $152 billion. “In comparison with other ecosystems, the restoration of coastal ecosystems such as deltas is among the most expensive,” Foufoula-Georgiou says.

Although researchers understand the risks to deltas, their knowledge of natural and human-caused processes in delta landscapes remains incomplete.

“We urgently need to understand the processes that make deltas susceptible to change, and to develop strategies for better management, protection and restoration of deltas,” Foufoula-Georgiou says.

World’s deltas not all alike

What makes that harder, she says, is that “deltas are enormously variable,” from urbanized systems, such as the Pearl River Delta in China and the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt Delta in the Netherlands, to less developed deltas, such as those of the Amazon River and Alaska’s Yukon River.

High-latitude deltas, such as the Yukon, Mackenzie in Canada and Lena in Russia, are sensitive to rapidly increasing Arctic temperatures, melting the permafrost on which many formed.

“By assimilating diverse sets of data for different deltas, we can start to predict how a delta is likely to respond to environmental changes,” says Foufoula-Georgiou.

Finding answers: Eyes in the skies, boots in the mud

Observations from satellites can tell scientists a lot about river networks, delta sediments, and floods over time. The data offer insights into deltas at local, regional and global scales, and at regularly repeated intervals, something that’s otherwise impossible to achieve, scientists say.

“We also need to test hypotheses and models by getting our boots wet in the mud — taking measurements on the ground,” Foufoula-Georgiou says.

Through studies in the GBM, Mekong and Amazon — three very different deltas — researchers affiliated with the Sustainable Deltas Project are finding out how different delta ecosystems respond to climate change, urban development and dam construction.

“A critical part of the work is analyzing how human communities are affected by changes in these deltas,” Foufoula-Georgiou says. “Ultimately, we need to accept change as inevitable, and be ready to adapt to it.”

For example, she says that people may need to alter where they live to adapt to new coastlines. “But such shifts can be challenging. Populations in many developing countries can’t easily move away from deltas due to economic reasons such as the need to grow rice and provide food.”

Foufoula-Georgiou hopes that results from the Sustainable Deltas Project will support sound decision-making about deltas and their future.

“The answers matter for the three deltas we’re studying — and for deltas across the globe.”

—

Cheryl Dybas,

NSF

(703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov

-

Deltas are home to more than half a billion people; here, Egypt’s Nile River Delta at night.

Credit and Larger Version -

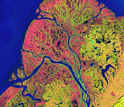

Scientists are studying the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta, which supports 150 million people.

Credit and Larger Version -

The Sundarbans in Bangladesh and West Bengal has the largest mangrove forest in the world.

Credit and Larger Version -

Birds from around the world migrate to Alaska’s Yukon Delta to nest and raise their young.

Credit and Larger Version -

A satellite view of oil trapped where the Mississippi River meets the Gulf of Mexico.

Credit and Larger Version

Investigators

Efi Foufoula-Georgiou

Related Institutions/Organizations

University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Related Awards

#1342944 Belmont Forum-G8 Collaborative Research: DELTAS: Catalyzing action towards sustainability of deltaic systems with an integrated modeling framework for risk assessment

Total Grants

$266,470